What We Can Learn From Adrian Newey's Office

I'm an F1 nerd. Get ready for a little F1 nerding out, but I promise it's on topic.

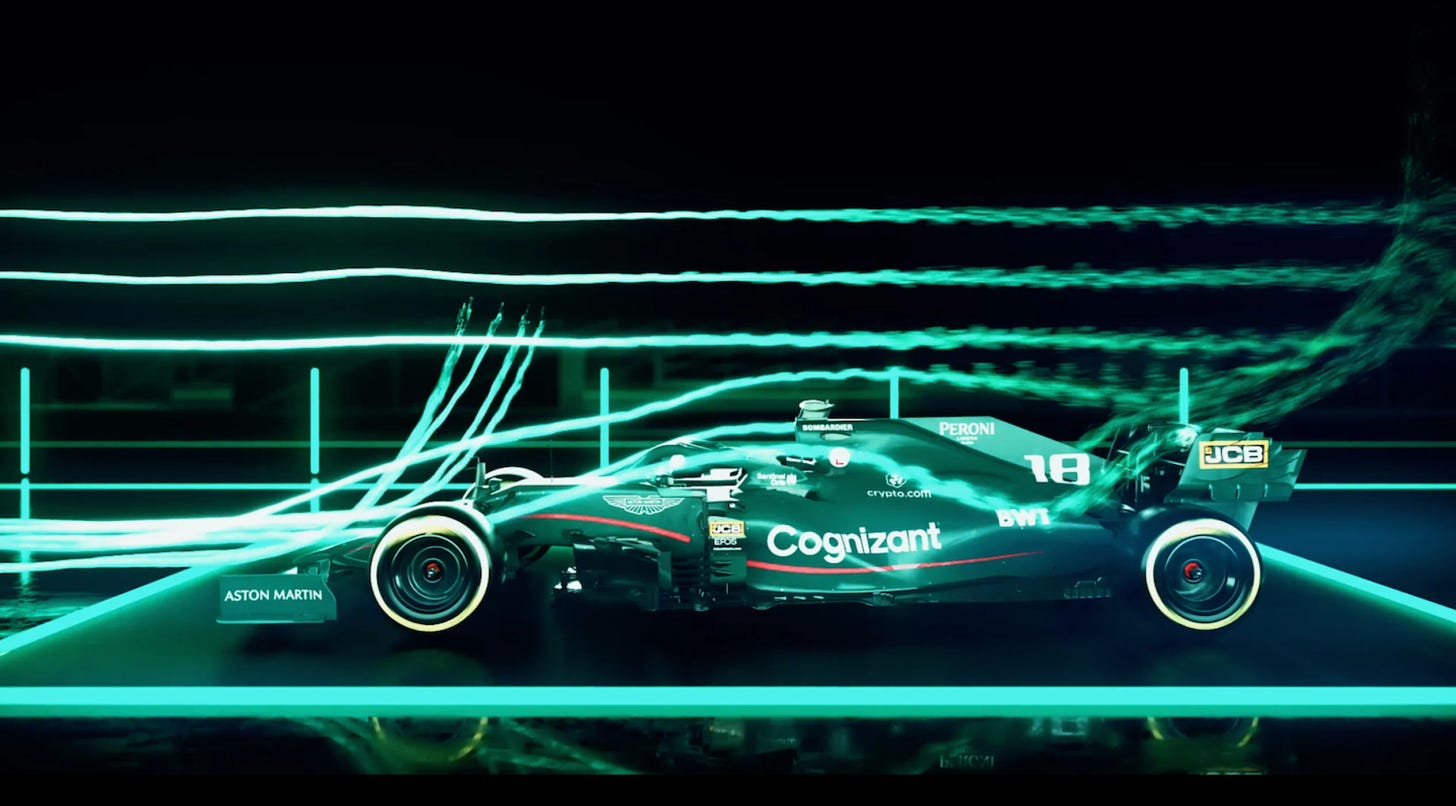

A couple weeks ago, Red Bull debuted their latest hypercar, the RB17. This thing is as sexy as it is brutal. It's a greatest hits track from the last several decades of Formula 1 which is, and I am highly opinionated here, the utmost pinnacle of motorsport. Red Bull combined the current ground effects downforce regime from the latest regulations with the siren sound of a V10 from 20 years ago and sprinkled in some active aero and other bits from other eras. Then they wrapped it in a sultry body that would make any runway model jealous.

Red Bull claims that this thing will match a modern F1 car around most tracks. For some perspective here on just how fast F1 cars are, here's an idea. Earlier this year a promising young driver named Ollie Bearman was called up from F2 to the Ferrari F1 team because Carlos Sainz had emergency surgery for appendicitis. This is an athletic 19 year old who drives a racecar with 500 hp and regularly pulls 3g in corners and under braking. Here's the before/after picture of Ollie's headrest for that race.

His neck whiplashed, unable to withstand the g forces, crushing the headrest. F1 cars are nuts. And the idea that Red Bull built a track-focused car for private use... That. Is. INSANE.

All of this came from the brain of Adrian Newey. Adrian is a legend in F1. He's been around for decades and has more championships than anyone else in the paddock. He's renowned and reviled equally for his ability to constantly be on the bleeding edge of the rules. Exhaust blown diffusers? That was him. The crazy seating position that allows better packaging and weight distribution? That was Adrian. Double diffusers? Him too. Insane DRS efficiency from low drag? Check. Which car has the best Y250 vortices? You better believe it's Adrian's.

Now let me show you Adrian's office and tell you why I think it's so great. Here it is:

Notice anything? Yeah, he doesn't use a computer much, or at least not first. And yeah, Adrian is old now but he's still the best. His primary tool is a gigantic drafting board. He's used the thing for decades. All of his concepts start here as he thinks about how air will flow through and around a racecar. He thinks about the car under load, under braking, at low speed, at high speed. Once the concepts are fluent, he works with his team to verify those ideas.

And here's why it's so interesting! F1 is insanely high tech. A modern F1 team is between 800 and 1,000 people with a $400mm yearly budget. CFD (Computational fluid dynamics) is one of the main keys of speed and the teams invest millions upon millions on the best wind tunnel and CFD setups.

And this dude is starting with a pencil and paper. Adrian is famous for walking the paddock with a sketchpad in hand so he's ready to draw out a new, clever idea he sees from another team or something that happens to strike him.

"It's not the tools you have faith in. Tools are just tools -- they work, or they don't work. It's the people you have faith in, or not." - Steve Jobs

We want to think we need the right tools. The thing holding us back is that we don't have the right monitor setup, the right version of Photoshop, or the most comprehensive CFD program. What Adrian's office reminds us is that what we really need are the right fundamentals, the right ideas, the right models, and intense effort and discipline pushing in the right direction. A computer won't give us that. Nor will an LLM.

Adrian isn't alone in his old world focus. The best across many fields use seemingly outdated tools for their work. George RR Martin writes in WordStar on a 30-year-old computer disconnected from the internet. Neil Gaiman writes with a fountain pen. Quentin Tarantino writes by hand in his notebooks. Many architects, like Renzo Piano, start with a pencil rather than CAD. When Jascha Heifetz wanted to evaluate the virtuosity of young violinist Itzhak Perlman, he asked him to play scales over and over.

The computer is a general tool. It can be adapted to do anything, which is is why software is eating the world. The problem is that we often adapt them wrong. They get in the way of what we're trying to do, or worse, serve as a crutch for our brains and thus eliminating our ability to inject the most important human component: vision.

"We shape our tools, and thereafter our tools shape us." - John Culkin

Tools matter a lot, we just need to put them in their place. An example I'm fond of are the hand planes of Japanese woodworkers. There are competitions for how long and how thin master woodworkers can plane a board of wood. These guys are basically creating tissue paper with a single pull of their blade.

If you gave me their hand plane and a few days, I would not have a prayer of pulling a ribbon like that. These tools enhance the skill of their master. They don't replace a skill or automate it away. They take a latent capability and make it more powerful.

Tools in the digital world can enhance skill instead of replacing it too. In software development, code editors handle some of the most complex operations humans do with a computer. And we see a similar philosophy at play. Vi and Emacs have been around for decades and are still favorites among good developers, and the more modern varieties follow many of the same principles. But there's one thing they never do: they never take focus away. These tools never lead the developer astray from their task, because the cost of losing context and attention for the programmer is so large.

When we choose our tools, this is the question we need to ask: does it enhance us or replace us? The answers to this question may be changing over time, but it's remarkable how many of the best talents across creative fields still focus on the fundamentals.

Behind every marvel like the RB17 stands a visionary, often armed with nothing more than a simple tool. Whether it's Adrian with his drafting board or a Japanese master with a hand plane, the lesson is the same: innovation comes not from the sophistication of our tools, but from the skill, vision, and dedication of those who wield them.

In our rush to embrace the latest and greatest of everything, we would do well to remember the power of fundamentals and the irreplaceable value of human creativity. The most innovative minds understand this intuitively. They recognize that the best ideas emerge from the simplest beginnings, uncluttered by technological complexity.

A piece of paper. A pencil. A drafting board. Adrian chose these because he knew what he needed to enhance and what he needed to focus on. He reminds us that the path to groundbreaking innovation often starts with the humblest of tools, leaving room for the most powerful instrument of all: the human mind.