I take no credit for this title. Yes, it is fantastic. Right on the money.

If you've been on Twitter in the last week, you're as tired as I am of Ghibli content. Ghibli. Ghibli. Ghibli. Every image is a Ghibli image. Erik Hoel says this is called semantic satiation. Ghibli. But I don't feel satiated, I feel spent. The word has lost its meaning. Ghilbli. Like I'll never appreciate Japanese animation again. Ghibli!

The first Ghibli image was cool. It was thoughtful. Full of care. An exercise in stretching new algorithmic abilities. But at some point along the way, it all becomes slop. Slop. Slop. Slop.

Slop has always existed but it took a revolution like AI to coin the term. Nabeel goes on to give a definition:

Slop is probably one of the most important & rich concepts for understanding modernity; slop is: 1) efficient 2) mass produced (low cost) 3) done carelessly, thrown together without fussing over the details 4) ahistorical; not rooted in tradition or practice

That's how the internet feels now. Like it's slop instead of turtles, all the way down.

What Have We Lost?

Do you remember the internet in 1999? Or 2003? Or 2007? There's a whole generation of people now that don't. People born in 2007 are voting and joining the military (but ridiculously NOT buying cigarettes or booze). This generation thinks the internet is a bunch of apps.

Back then the internet was exciting because it involved discovery. Google existed, but you had to have some skill to use it unless you just liked the "I'm Feeling Lucky" button. You could go 2 and 3 levels deep on Facebook and figure out who knew who knew who. Interesting people had blogs they had to host themselves. It took effort to stand up your own domain and write or make art or a website.

In college, a roommate or a friend would show you these amazing things they found on the internet. They'd tell you to pull up a chair in front of their desktop so you could laugh together over a video or see the latest game. Or they'd chat you over IM. With a full size keyboard. Or a phone call. Sometimes what they showed you was stupid. And sometimes it changed your world.

Paul Graham grew famous in this way. Computer Science students across the world discovered his essays and they traversed the programming population more slowly via email or text or conversation. Paul started YCombinator in 2005. Before Twitter. Before Facebook was open to the public. Before Hacker News. Before smart phones. YCombinator spread through people. Sam Altman heard about it from a friend down the hall in his dorm and decided to apply.

Information in this era passed through people rather than algorithms.

Frictionless Revolution

Much of the work of the internet since the Aughts has been about removing inconveniences. It is inconvenient to go to a store to rent movies (Netflix). It is inconvenient to share life individually with friends and family (Facebook). It is inconvenient to drive to a restaurant to pick up food (DoorDash). And we’ve got digital dollars, steaming music, online maps, and virtual taxis too. All very convenient.

We've dropped the cost of discovery to zero. You can find any music on Spotify. Any video on Youtube. Any phrase and idea on Twitter. If discovery is costless, we're incentivized to make more content and to see more content. Whether it is any good matters less. We don't care. AI generated is just as good as human content, as long as it's seen and heard and viewed. Slop. Slop. Slop.

I've talked before about how most of the technology of the last twenty years has been about connection and compression. Removing inconveniences is about eliminating the friction in connection. When everything is connected, the friction drops to zero.

Zero is too far. A little friction can be a good thing. A little effort demonstrates will. The Jonathan Haidt social media counter-revolution had us discovering this on our own, but AI has accelerated our awareness. In 2025 it seems like most of the content we encounter is AI slop and — just to keep up — the actual humans are making more slop too. Get ready for a Slop summer.

The Algorithms

Discovery started to become costless when Facebook invented the Like button in 2009. The world exploded with thumbs and hearts and retweets and 🤣 emoji. Sharing and reacting was easy, so easy you could count them! And so we built algorithms on top of likes and hearts and this is how the algorithms came to rule the kingdom of content with an iron fist.

Today the issues lie not with people reacting to these algorithms but with the algorithms themselves. When the feedback loop is cheap, everything looks like slop.

The algorithms are strong. Cheap feedback loops are here to stay. As Packy McCormick says, we're culturally driving towards an era of Hyperlegibility. The world is hooked on super low cost discoverability. If we’re not swiping for the next reel, we’re posting it ourselves and counting the likes. We're making everything, including ourselves, as legible as we can.

So what are we to do?

One thing we can do is to allow the act of discovery to have a price again, rather than be completely free. Much like the idea of paying $1 to apply for a job, even a de minimus cost will transform the quality of what gets created. Algorithms don’t want to pay to create, but humans can. When there’s a cost, information starts passing through humans again. Worried about Slop? Don't allow creation to get homogenized away into nothing.

Costs aren't necessarily measured in dollars, although this is the easiest go-between for supply and demand. One highly underrated aspect of Substack as a platform is that it incentivizes Care. Yes, there's plenty of mediocre writing here. Yes, there's mediocre ideas too. But there's also a reason that all the best thinkers and all the best writers are gravitating here. You won't find many posts here under 140 characters. You won't find Slop. The platform expectation is that you're putting some effort in. This has a remarkably high amount of signal. Even the Notes section, which is effectively like Twitter on Substack, is high quality.

Creation on systems with careful incentives reward Care. They reward creation and beauty, even if it sometimes means giving up on audience. On reach.

When things are free, as the old trope says, then you are the product. The algorithms have no incentives to be careful. They only want more eyeballs. They are purely democratic in the sense that they care very little about which content goes viral. Slop. Slop. Slop. They only care that it goes viral. More views means more eyeballs. More eyeballs means more advertising.

Care-ful

Despite all of this, I'm surprisingly bullish on the direction we're going. The idea of most cost functions asymptoting towards zero has tremendous economic power. As Alfred North Whitehead quipped: "Civilization advances by extending the number of important operations which we can perform without thinking of them."

And there's a huge rebellion at work against the algorithms. People are realizing that they no longer own the communication channels through which culture is passed. They're learning how to navigate this new world, opting out of it wherever they can and leveraging it wherever they must. Packy McCormick sees a new generation of students as remarkably adept in this hyperlegible world. And so he asked one of them "why so many of his peers seemed so scarily advanced":

His answer was that they grew up on the internet, with access to all of the information imaginable. Not just the fire hose, but the blogs and newsletters and podcasts and YouTube videos that helped make sense of the stream. So it was easy for a relatively curious kid to figure out what to read to set a baseline, and then, baseline established while the brain is still fresh and curious, to jump off of that base of knowledge to ask their own questions. To help answer them, they have all of the internet’s information, AI, and even one-DM-away access to experts.

People want to be capable. Powerful. And they want to be careful. Care-ful. As in, full of care. We've spent at least a decade of culture trying to teach us to be harmless. But being careful is different. You cannot be careful if you are powerless. You can only be careful if you are a threat. If you could exert great harm but choose and work not to.

As Mr. Beaver said about Aslan: "Safe? Who said anything about safe? 'Course he isn't safe. But he's good."

Being careful requires power. The more power, the more care-ful.

Culture is already moving in a care-ful direction. Away from slop and towards power. Moving to a dumb phone is care-ful. Growing a garden is care-ful. Curiosity-driven learning is care-ful. Focusing on long form conversations is care-ful. Having expert mentors and strong networks is care-ful. Building institutions is care-ful. Contributing to your local town is care-ful. Building non-VC companies is care-ful.

Care. Care. Care.

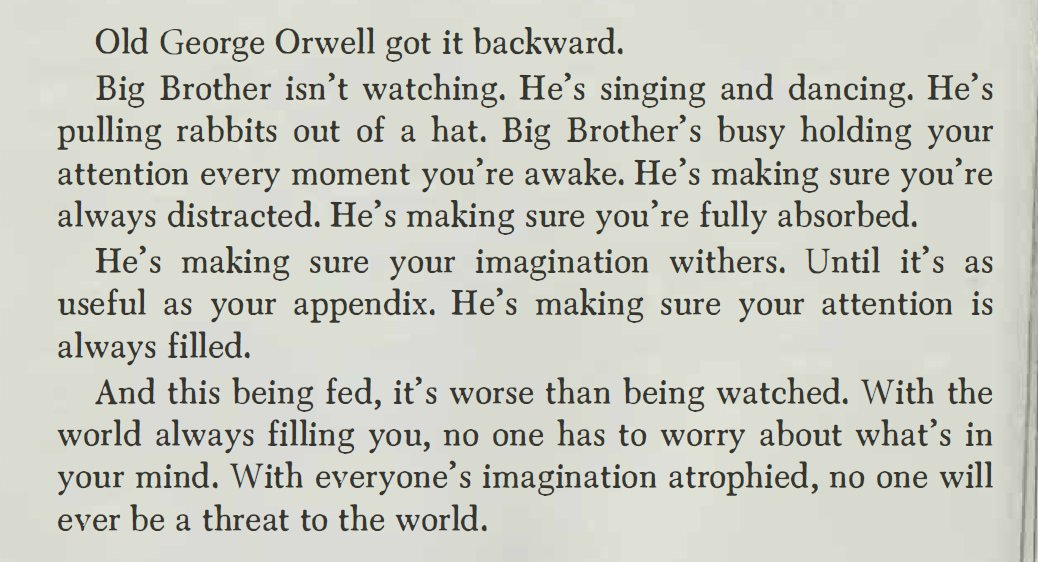

There's more to be done, and we continue to need better systems. I read 1984 last year. Yes, for the first time. I'll leave you with this incredible twist on Orwell from Fight Club author Chuck Palahniuk.

“The world” today is represented more and more by the algorithms. The algorithms make us harmless. Our goal should be to make ourselves a threat to this world. To be dangerous, but good. To hold power and exercise care.

And use that power to make the world better. The opposite of slop is care.

Or not. You could just keep swiping.

References: (you should read these, they’re all amazing)