You must change your life.

These five words have haunted me this past year. They speak not of gentle self-improvement or casual promises, but of demanded transformation. This demand is still in my head now, as 2025 dawns and millions of us engage in the ritual of resolutions. I've been doing New Year's Resolutions for about ten years. It was a dramatic shift for me and has become a force of both reflection and change.

I used to be one of those unserious people who scoffed at resolutions, suggesting like so many others that if you really wanted to make a change in your life that you can do it any day you wish. January 1 is an arbitrary choice and just a day like any other. This argument seems just as considered as suggesting we try Christmas in April or move the US capital to California. Not everyone who skips resolutions scoff at the idea. Some people don't think much about it at all. And then there are those rare super high agency people who really don't need them, because they see a needed change and immediately start marching towards it. I think there are very, very few of those people.

The new year is a time for new beginnings, and some of the power is in the arbitrary commons of the date. We all wait for the ball to drop. We all start training our brains that it really is 2025. We all start over in some way. We all stop to celebrate. When we stop, we’re offered the chance to let reality tell us something about ourselves.

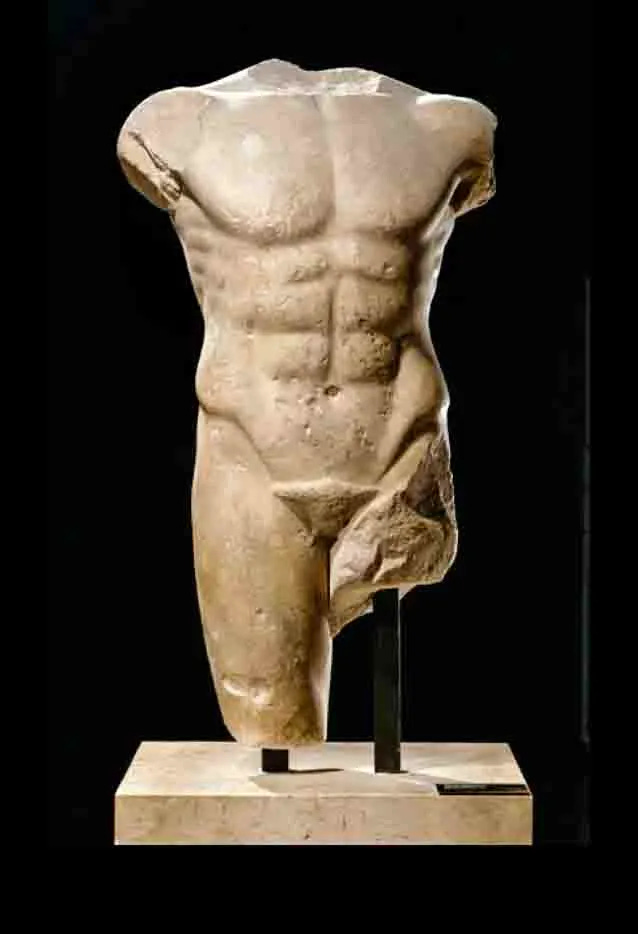

About a year ago, I encountered Rilke's Archaic Torso of Apollo. The poem describes a broken statue, headless and ancient, yet somehow radiating an impossible vitality. I read it over and over and over. What seized me wasn't just Rilke's imagery, but the shocking final line that seems to come from nowhere and everywhere at once:

You must change your life.

What makes this command so powerful, as Douglas Murray beautifully articulates, is that it emanates not from the viewer's mind but from the statue itself. The broken torso of Apollo speaks. And it isn't a gentle nudge — it is beauty reaching out and demanding transformation. The statue blazes with such power that we cannot remain unchanged in its presence.

You must change your life.

In some way 2024 was for me an ongoing meditation on this poem. The idea that truth and beauty might have something to say to us - that they are active forces in the world rather than absorbed passively - is antiquated to the modern man. It is a discarded childhood toy laying dusty near a baseboard in the corner of our room. We remember it only occasionally, too busy rushing past enraptured in our own maturity. Our culture has only a vague memory of the triumph and emotion that truth and beauty once had. Their glory has faded, their greatest generational prophets - ironically, those steeped in the terror and despairs of the 20th century - are old and dying.

It’s up to us now.

Someone once said that the distance between your dreams and reality is action. This is the metamorphosis proposed to us by truth and beauty. Reality is begging us to use our agency and bring about the world of our dreams. The evolving questions from the Greeks to the Enlightenment have all been questions of curiosity. What is the purpose of reality? Of truth and beauty? Of evil? Of suffering? Of ourselves? The universe is the Answer, but - as Douglas Adams and Elon Musk suggest - perhaps we haven’t compiled all the right questions yet. Our privilege as humans is that we have agency to help shape both the answers and the ongoing questioning.

The critical debate of our time is: do we even acknowledge these questions? Rushing around late to our meetings while staring down at the videos on our screens, are we capable of hearing through our headphones the message the statue of Apollo whispers to us? Or is our attention too saturated and too divided to even recognize that truth and beauty exist? The modern human impulse is not an outward motion towards reality, but an inward sweep towards a virtual hologram. We live today in a digital panopticon of our own shared making, a modern-day Cave filled with shadows more alluring than Plato could have imagined, where desire and acceptance are more important than virtue or goodness.

We need to change. I need to change. This idea of change is not one that divides humans into groups; they are ideas that divide our hearts. We each have a side that is yearning to listen for the divine whispering in our everyday reality. And we have another side, eager for dopamine, ready to be molded into what the mob demands of us. Each side is an animal ravenous for the activity, attention, and exercise that will help it grow. Which animal will be fed?

You must change your life.

Listen to what I shall call Him: the Bottomless Abyss, the Insatiable, the Merciless, the Indefatigable, the Unsatisfied. He who never once said to poor unfortunate mankind 'Enough!'

'Not enough,' that is what he screamed at me.

'I can't go further,' whines miserable man.

'You can!' the Lord replies.

'I shall break in two,' man whines again.

'Break!'

— St. Francis by Nikos Kazantzakis