This is Part 2 in a series on the changes that have made us into cyborgs.

No GPS

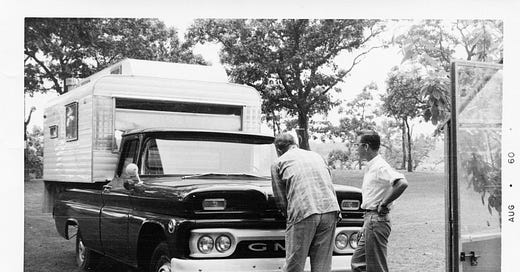

In 1960, John Steinbeck was 58 and had already won the Pulitzer Prize. He had made his mark on the literary world writing about the American experience but felt that he had lost touch. So Steinbeck set out on a trip across the country to rediscover the America he had forgotten. He took with him a very American level of wanderlust, his ten year old “blue” poodle Charley, and a custom camper he ordered named Rocinante.

The result is a delightful little book called Travels with Charley. Steinbeck starts it off at his home in Sag Harbor, NY with the provisioning process of his camper. He packs food, clothes, a pile of “all the books you never get around to reading”, tools, spare parts, and maps of the country. He only crosses one state line before he gets lost for the first time. By the time he reaches Maine - just a couple states away - he’s backtracked many times. But he’s also met farmers and waitresses and others, none of whom know who he is.

It’s important to think about exactly what this trip must have been like in 1960. Here’s a very incomplete list of how it was different.

Camping on a farm meant that when it was dark, it was really dark. There were no batteries or LEDs or much of anything aside from maybe a kerosene lamp.

You were not connected to anything or anyone, unless you drove or ran to the nearest farmhouse.

There were no movies to watch, no Instagram to catch up on, no Inbox, no texts to respond to.

When you were driving, you had only the resolution of the paper maps you had with you to figure out where you were going. If you switched states it meant grabbing a new map.

Which is assuming you actually knew where you were! There was no GPS to tell you.

You had to think ahead about where a gas station might be along the highway.

If you had a problem, finding a mechanic - or a ride to town to start looking for a mechanic - was a crapshoot. Once you found the mechanic, there was no telling how reliable or trustworthy they may be.

There was no electricity and no signal. There was no connection to anything, unless you were near a building that had electricity and a landline.

Describing this in today’s always connected world makes it sound like it was the 1700s. And in some ways, it was. The middle of the 20th century represents an odd in-between time joining the connected world of today and the rest of human history. The infrastructure for our connected world was there - there were phone lines and TVs and interstate highways - but it still took a few decades and a few new technologies to make it the ubiquitous and everpresent experience we live in.

Even more striking when reading Steinbeck’s travel journal is that he travels the country anonymously. Nobody knows who he is and he doesn’t volunteer the information. Nobody wants a selfie or an autograph. His movements aren’t tracked. His wife knows where he is only if he writes a letter or makes an expensive phone call. Unless he chooses to make a connection, he is entirely on his own. His default state was “disconnected”.

Our default state today is the opposite. Parents buy their kids a phone so they know where they are after school, forgetting that they themselves were never accounted for in the same way. Email and chat connect employees who make themselves available at any time day or night. Friends can text and chat each other hourly if they want.

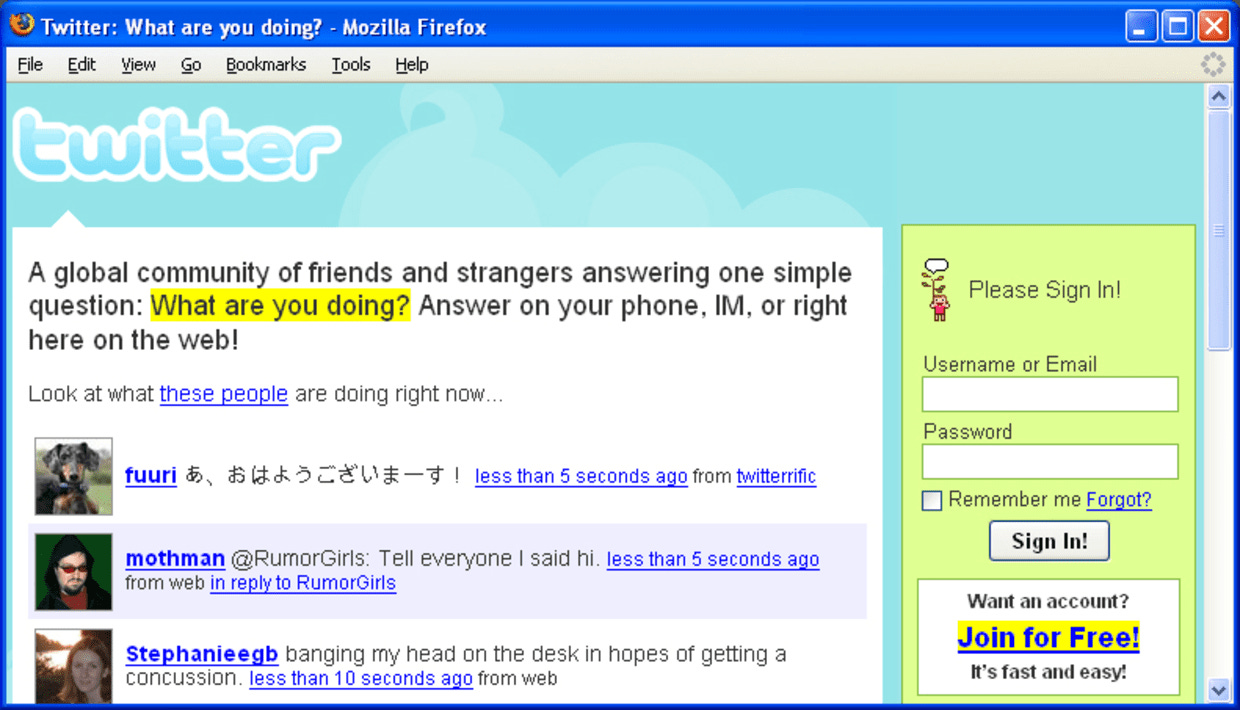

Twitter’s original UI tagline was “what are you doing?”. This originally novel idea of status updates has spread to every social media platform. Just over 15 years later, we’re programmed to make sure our followers knows what we’re up to, and we glory in the chance to post our content.

But even way back in 1960, Steinbeck believed that he was already living in a very different world than the past. Here’s his accounting of the difference:

There was a time not too long ago when a man put out to sea and ceased to exist for two or three years or forever. And when the covered wagons set out to cross the continent, friends and relations remaining at home might never hear from the wanderers again. Life went on, problems were settled, decisions were taken. Even I can remember when a telegram meant just one thing - a death in the family. In one short lifetime the telephone has changed all that. If in this wandering narrative I seem to have cut the cords of family joys and sorrows, of Junior’s current delinquency and junior Junior’s new tooth, of business triumph and agony, it is not so. Three times a week from some bar, supermarket, or tire-and-tool-cluttered service station, I put calls through to New York and reestablish my identity in time and space. For three or four minutes I had a name, and the duties and joys and frustrations a man carries with him like a comet’s tail. It was like dodging back and forth from one dimension to another, a silent explosion of breaking through the sound barrier, a curious experience, like a quick dip into a known but alien water.

We’ve transitioned yet again, far beyond what Steinbeck could have imagined. In the last 10 or 15 years - in far less than the span of one short lifetime - we have built a new world where our identity in time and space is broadcast around the clock. Steinbeck’s travelogue demonstrates how our confidence and our adventures have both atrophied. Our confidence is tightly wound around the opinions of others. We can’t do anything anymore without making sure other people know about it. We can’t walk out the front door without checking in at designated checkpoints. The Likes and Hearts and status messages and pings provide us fresh new validation of our place in the interconnected web of status around us.

There’s a beautiful scene in the movie Space Cowboys where Clint Eastwood’s character finally achieves his dream of spaceflight and hovers on a spacewalk in orbit over the Earth for the first time. The beeps and messages from his suit pause for a few seconds and he turns so that he can’t see the Space Shuttle behind him. In the frame he is completely alone. Attached to nothing, silent. It’s a beautiful scene because the space program is so driven by repetitive and process-driven engineering. Eastwood is wrapped in a high tech suit with an ever present audio connection in his ear. The space program needs to be this way because space will kill you quick.

We live in a similar cocoon of stimuli, awash in data and status and communication. The room for privacy and silence is short. Seeing an astronaut awash in data and process and stimuli have a moment of grandeur resonates with the freedom we sometimes hope for. The freedom that Steinbeck had. That the whole world once took for granted as normal.

Real Risk

Our new default connected state has changed how we interact with risk too. To put it bluntly, there’s less of it. Our daily lives hold minimal risk compared to even fifty years ago. We’ve had a steady march of forward progress on safety for a long time. The Insurance Institute for Highway Safety did an incredible crash test between a 1959 and 2009 Chevy Impala just to underline the point. The older car crumples exactly like the hulk of metal that it is and shreds the dummy inside. Meanwhile, the new car surrounds the dummy in a magic bubble of airbags and aluminum frame so that he “walks away” without a scratch. It isn’t just cars, it’s everything from GFI electrical outlets to safer paint to safer fences to better government regulations.

None of this is a bad thing. Lowering the risk of death has sweeping positive consequences. It’s changed the risk of smaller setbacks too. Expertise across industries is spread out. Before YouTube, a broken appliance or a busted fuse in your car might mean a day off to wait for the repairman or an expensive tow to a mechanic. But today the solution is a Google search away. When something goes wrong, the path to fix it is simpler and the chances of being taken advantage of by an expert are much lower.

Even more interesting is how our connectedness also changed our perception of risk. There’s a new cult of ‘safetyism’ that tells us to protect our children and look out for every 1-in-a-million possible danger. And we worry just as much about emotional safety as we do physical. Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt break this down in their book The Coddling of the American Mind. Being unwilling to make tradeoffs around safety and other practical and moral concerns is interfering with people’s social and intellectual development.

Even though we want our lives to be perfectly safe, we crave the perception of risk too. There are now whole industries working to manufacture perceived risk for their customers. Skydiving used to be the ultimate daredevil’s thrill. I can count plenty of friends that have done it on a whim. And what is the point of a Spartan race or a Tough Mudder if not perceived risk? Spartan’s call to action implies your existing lack of risk: “The first day of your new life starts here.” It’s a call to come get dirty with us, feel some manufactured risk, then have a beer and laugh about it afterwards.

We have all the reassurance we could possibly need and none of the balls.

The value missing from our connected lives is competence. We’ve outsourced it to the crowd so that we can call on any number of skillsets at a whim. At a high level, this is still an advantage and the continuing march of specialization. All of us are able to gain more leverage across a larger diversity of skills. But our diversification has limited our own competence, or our own feeling of competence. Competence can be measured by the probability of succeeding when there’s a real chance of failure. It’s why we call a real mechanic when our armchair mechanic skills fail. There’s more to being a mechanic than just looking up information and following instructions.

Nearly everyone that enters a Tough Mudder finishes a Tough Mudder. It’s designed to feel hard but still let everyone through. And to be clear, there’s nothing wrong with a boost of confidence and a first step. But we do ourselves a disservice if we calculate our perceived risk as real risk. If we want the very human quality of competence, we need to step into the realm of real risks.

In the movie Free Solo, we watch Alex Honnold put his life on the line to climb El Capitan with no rope. The movie focuses not just on the climb, but on the journey he takes to make himself capable of doing it. Alex is relentless in both his physical and mental preparation. He spends hours on the route cleaning and prepping the surface so that everything is perfect. He memorizes every hand and foot movement on the entire 3,000 ft. route. He climbs it with a rope over and over until it is second nature. He leaves nothing to chance.

And still the risk is palpable. The camera crew - his friends - can barely watch as he moves from hold to hold on the sheer surface. I don’t even know him and I could barely watch.

There’s only one Alex Honnold in the world, and he will be the first to tell you that what he does is extreme. But we’re drawn to his example because he’s willing to prove his competence against a very real risk. He believes in his own competence more than the risk. This is what is so compelling about Alex Honnold. His attitude is the same as the 19th century settlers leaving their families in covered wagons to set out across the continent.